The Winding Road to Nourishment

Why Our Intestines Are Like a Marathon, Not a Sprint!

The mysteries of the human body, a veritable symphony of biological marvels! Today, my curious young naturalists, we delve into a question that might have tickled your intellect: why, oh why, do we possess such wonderfully long intestines? It's a query that often elicits a chuckle, perhaps even a whimsical image of our internal plumbing stretching for miles. But rest assured, there's a profound, biologically sound reason for this incredible anatomical marathon.

Imagine, if you will, the culinary journey your breakfast embarks upon. A perfectly toasted slice of bread, perhaps a scrambled egg – these aren't simply absorbed whole. Oh no, the body, in its infinite wisdom, must meticulously dismantle them, molecule by molecule. This process, known as digestion, is not a rapid dash, but rather a slow, deliberate waltz.

Think of your small intestine, a remarkable tube, typically around six to seven meters (that's roughly 20 to 23 feet!) in an adult, as the ultimate digestive processing plant. It's here that the heavy lifting occurs, where the complex carbohydrates, proteins, and fats are broken down into their simpler, absorbable forms. Those proteins from your egg, for instance, are cleaved into individual amino acids by enzymes like pepsin and trypsin. The bread's starches? They're meticulously hydrolyzed into glucose by amylase. This chemical transformation, this intricate dance of enzymes and substrates, takes time. Lots of time!

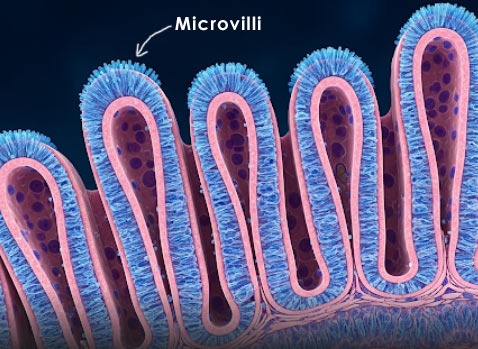

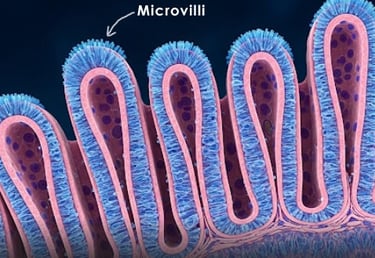

And this is precisely where length becomes our greatest ally. A long path ensures ample opportunity for this molecular deconstruction and subsequent absorption. The inner surface of your small intestine isn't smooth; it's a magnificent landscape of folds, called plicae circulares, studded with tiny finger-like projections known as villi, which in turn are covered in even tinier microvilli. This astounding architecture creates an enormous surface area – imagine unfurling it, and it would cover a tennis court! This vast expanse is crucial for efficiently drawing nutrients, vitamins, and minerals into your bloodstream. If our intestines were a mere stubby pipe, precious nutrients would simply rush by, unabsorbed, a truly wasteful endeavor.

Once the small intestine has expertly extracted the valuable nutrients, the remaining, undigestible material embarks on the next leg of its journey into the large intestine, or colon. This wider, shorter segment, typically about 1.5 meters (5 feet) long, is a master of dehydration and waste consolidation. Here, water and electrolytes are reabsorbed back into the body, transforming the liquid chyme into a more solid form. It's also home to trillions of beneficial bacteria, our very own internal ecosystem, the gut microbiome. These microorganisms play a vital role, synthesizing certain vitamins (like Vitamin K and some B vitamins) and further breaking down indigestible fibers, a process that can produce gases – a natural consequence of their diligent work!

Finally, the journey culminates in waste excretion. The now-solid waste, or feces, is propelled towards the rectum by waves of muscular contractions known as peristalsis, a rhythmic squeezing motion that moves material through the entire digestive tract. This culmination is just as vital as the initial digestion, ensuring that what the body doesn't need is efficiently removed, maintaining our internal balance.

And it’s not just us! From the majestic lion to the humble earthworm, the vast majority of animals possess intestines of considerable length. Herbivores, like the cow with its multiple stomachs and incredibly long intestines, need even more time to break down tough plant fibers like cellulose. Even carnivores, despite their protein-rich diets, require a significant length of gut to extract every ounce of nourishment.

Now, considering this continuous internal marathon, you might wonder if these tireless organs ever get a break. And indeed, they do benefit from a little respite! While our digestive system is designed for continuous operation, incorporating a very light meal once or twice a week, or even skipping a meal entirely (always consult your doctor before making significant dietary changes, especially if you have underlying health conditions!), can offer certain advantages. This period of reduced activity allows the intestinal lining to regenerate, potentially reducing inflammation and giving the various digestive enzymes and cells a chance to "reset." It's a bit like giving a hardworking engine a brief cool-down period – it can contribute to overall efficiency and longevity.

So, the next time you ponder your internal workings, remember the magnificent marathon taking place within. Our long intestines are not a design flaw, but a testament to the elegant efficiency of evolution, ensuring that every morsel of food provides the energy and building blocks we need to thrive, and that waste is efficiently managed. Truly, a remarkable feat of natural engineering, continuously working for our well-being!